Contacts

Info

The Story of Passover: A Tale of Liberation, Faith, and Tradition Passover, also known as Pesach in Hebrew, is one of the most significant and widely celebrated Jewish holidays. This...

show morePassover, also known as Pesach in Hebrew, is one of the most significant and widely celebrated Jewish holidays. This annual festival commemorates the liberation of the Israelites from slavery in ancient Egypt, as described in the biblical book of Exodus. The story of Passover is a powerful narrative of faith, perseverance, and divine intervention that has been passed down through generations, shaping Jewish identity and tradition for thousands of years.

The Israelites in Egypt The story of Passover begins with the Israelites, descendants of Jacob, living in Egypt. As recounted in the Book of Genesis, Jacob's son Joseph, who had been sold into slavery by his jealous brothers, rose to become a powerful figure in Egypt, second only to Pharaoh. During a severe famine, Joseph's family, including his father and brothers, came to Egypt seeking food and refuge. They settled in the land of Goshen and prospered, growing in number over the years.

However, as time passed, a new Pharaoh came to power who did not know of Joseph or his contributions to Egypt. This Pharaoh, feeling threatened by the increasing population and influence of the Israelites, subjected them to harsh labor and oppression. The Egyptians forced the Israelites to work as slaves, building cities and monuments for Pharaoh. Despite their hardships, the Israelites continued to multiply, which only intensified Pharaoh's fear and cruelty.

The Birth and Calling of Moses During this time of oppression, a boy named Moses was born to an Israelite family. In a desperate attempt to save her son from Pharaoh's decree that all male Hebrew infants be killed, Moses' mother placed him in a basket and set him afloat on the Nile River. Pharaoh's daughter discovered the child and, moved with compassion, decided to raise him as her own in the royal palace.

As Moses grew up, he became aware of his true identity and the suffering of his people. One day, he witnessed an Egyptian beating an Israelite slave and, outraged, killed the Egyptian. Fearing for his life, Moses fled to the land of Midian, where he married Zipporah and became a shepherd.

Years later, while tending to his flock, Moses encountered a burning bush that was not consumed by the flames. From the bush, God spoke to Moses, revealing His plan to deliver the Israelites from slavery and lead them to the Promised Land. God instructed Moses to return to Egypt and confront Pharaoh, demanding that he let the Israelites go.

The Ten Plagues Moses, along with his brother Aaron, went before Pharaoh and delivered God's message: "Let My people go." However, Pharaoh's heart was hardened, and he refused to release the Israelites from bondage. In response, God sent a series of ten plagues upon Egypt to demonstrate His power and compel Pharaoh to change his mind.

The ten plagues were:

1. Water turning to blood 2. Frogs 3. Lice 4. Wild animals 5. Pestilence 6. Boils 7. Hail 8. Locusts 9. Darkness 10. Death of the firstborn

Each plague brought increasing devastation and suffering to the Egyptians, while the Israelites were spared. Despite the mounting pressure, Pharaoh remained obstinate, refusing to let the Israelites go until the tenth and most terrible plague struck.

The Passover and the Exodus Before the tenth plague, God instructed Moses to have each Israelite family select a year-old male lamb without blemish, slaughter it at twilight, and apply its blood to the doorposts and lintels of their homes. They were to roast the lamb and eat it with unleavened bread and bitter herbs, dressed as if ready for a journey, with sandals on their feet and staffs in their hands. This meal became known as the Passover Seder.

On that fateful night, the Angel of Death passed through Egypt, killing the firstborn of every Egyptian household, from the lowliest servant to Pharaoh's own son. However, the angel "passed over" the homes marked with lamb's blood, sparing the Israelite firstborns. This final plague broke Pharaoh's resolve, and he finally agreed to let the Israelites go.

In haste, the Israelites gathered their belongings and prepared to leave Egypt, taking with them the dough for their bread before it had time to rise. This is why, to this day, unleavened bread (matzah) is eaten during Passover as a reminder of the Israelites' swift departure from Egypt.

Led by Moses and guided by God in the form of a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night, the Israelites began their journey to freedom. However, Pharaoh's heart was once again hardened, and he pursued the Israelites with his army, cornering them at the edge of the Red Sea.

In a dramatic display of divine power, God instructed Moses to stretch out his staff over the sea, causing the waters to part and allowing the Israelites to cross on dry ground. When the Egyptians attempted to follow, the waters crashed back down, drowning Pharaoh's army and securing the Israelites' escape.

The Significance of Passover The story of Passover holds immense significance for the Jewish people, both as a historical event and as a spiritual metaphor. On a literal level, the Exodus marks the birth of the Israelites as a free nation, liberated from the bonds of slavery and set on a path to the Promised Land. This narrative of redemption and divine intervention has served as a source of hope and inspiration for Jews throughout history, particularly during times of persecution and hardship.

On a deeper level, Passover represents the universal human struggle for freedom and the triumph of the oppressed over their oppressors. The story of the Israelites' liberation from Egypt has resonated with people of all faiths and backgrounds, serving as a powerful symbol of the fight against injustice and the pursuit of human dignity.

Moreover, the Passover story emphasizes the importance of faith, obedience, and trust in God. Throughout the narrative, Moses and the Israelites are called to rely on God's guidance and protection, even in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles. This message of unwavering faith and the power of divine providence has been a cornerstone of Jewish belief and practice for millennia.

Passover Traditions and Observances The Passover story is not only retold but also relived through a rich tapestry of traditions and observances that have developed over centuries. These customs serve to maintain the connection between contemporary Jews and their ancestral past, ensuring that the lessons and significance of the Exodus are passed down from generation to generation.

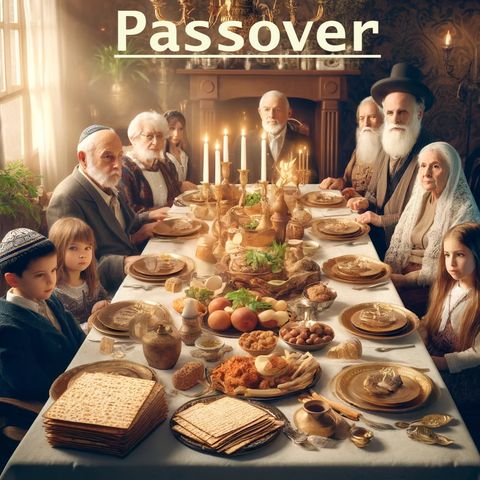

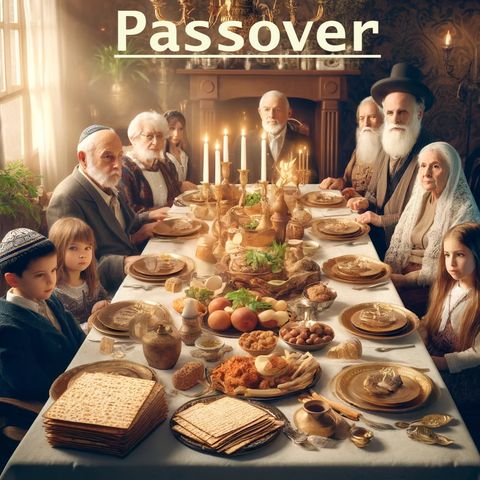

The Passover Seder The centerpiece of Passover celebrations is the Seder, a ceremonial meal held on the first night (and sometimes the second night) of the holiday. The Seder follows a specific order of rituals and readings, as outlined in the Haggadah, a special text that guides participants through the evening.

During the Seder, families and friends gather around the table to partake in symbolic foods, recite prayers and blessings, sing songs, and discuss the story of the Exodus. The Seder plate, a central feature of the meal, contains six items that represent different aspects of the Passover narrative:

1. Zeroa - A roasted shank bone symbolizing the Paschal lamb 2. Beitzah - A hard-boiled egg representing the festival sacrifice 3. Maror - Bitter herbs, usually horseradish, symbolizing the bitterness of slavery 4. Charoset - A sweet paste made of fruits and nuts, representing the mortar used by the Israelite slaves 5. Karpas - A vegetable, typically parsley, dipped in salt water to symbolize the tears shed by the Israelites 6. Chazeret - Another bitter herb, often romaine lettuce, used in the Hillel sandwich

Throughout the Seder, participants drink four cups of wine, each corresponding to one of the four expressions of redemption mentioned in the Book of Exodus. They also eat matzah, the unleavened bread that recalls the haste with which the Israelites left Egypt.

One of the most engaging aspects of the Seder is the asking of the Four Questions, traditionally recited by the youngest child present. These questions highlight the unique features of the Passover meal and serve as a springboard for discussing the significance of the holiday and the Exodus story.

Passover Dietary Restrictions In addition to the Seder, Passover is marked by a set of dietary restrictions that commemorate the Israelites' hasty departure from Egypt. For the duration of the holiday, Jews refrain from eating chametz, any food made from leavened grains (such as wheat, barley, rye, oats, and spelt). This includes bread, pasta, cake, and most baked goods.

Instead, Jews eat matzah, a flat, unleavened bread made from flour and water, which is baked quickly to prevent it from rising. Many families also have special Passover dishes and utensils that are only used during the holiday to avoid any contact with chametz.

The prohibition against chametz serves as a powerful reminder of the Israelites' exodus and the importance of humility and simplicity. By forsaking the "puffed up" nature of leavened bread, Jews symbolically reject the ego and arrogance that can lead to oppression and injustice.

Counting the Omer Passover also marks the beginning of the Counting of the Omer, a 49-day period that links the holiday to Shavuot, the festival commemorating the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai. Each night, Jews recite a blessing and count the days and weeks until Shavuot, reflecting on the spiritual journey from physical freedom to the receiving of divine wisdom.

The Enduring Message of Passover The story of Passover and its associated traditions have endured for thousands of years, transcending time and place to offer a timeless message of hope, resilience, and the power of faith. In every generation, Jews are encouraged to

The Story of Passover: A Tale of Liberation, Faith, and Tradition Passover, also known as Pesach in Hebrew, is one of the most significant and widely celebrated Jewish holidays. This...

show morePassover, also known as Pesach in Hebrew, is one of the most significant and widely celebrated Jewish holidays. This annual festival commemorates the liberation of the Israelites from slavery in ancient Egypt, as described in the biblical book of Exodus. The story of Passover is a powerful narrative of faith, perseverance, and divine intervention that has been passed down through generations, shaping Jewish identity and tradition for thousands of years.

The Israelites in Egypt The story of Passover begins with the Israelites, descendants of Jacob, living in Egypt. As recounted in the Book of Genesis, Jacob's son Joseph, who had been sold into slavery by his jealous brothers, rose to become a powerful figure in Egypt, second only to Pharaoh. During a severe famine, Joseph's family, including his father and brothers, came to Egypt seeking food and refuge. They settled in the land of Goshen and prospered, growing in number over the years.

However, as time passed, a new Pharaoh came to power who did not know of Joseph or his contributions to Egypt. This Pharaoh, feeling threatened by the increasing population and influence of the Israelites, subjected them to harsh labor and oppression. The Egyptians forced the Israelites to work as slaves, building cities and monuments for Pharaoh. Despite their hardships, the Israelites continued to multiply, which only intensified Pharaoh's fear and cruelty.

The Birth and Calling of Moses During this time of oppression, a boy named Moses was born to an Israelite family. In a desperate attempt to save her son from Pharaoh's decree that all male Hebrew infants be killed, Moses' mother placed him in a basket and set him afloat on the Nile River. Pharaoh's daughter discovered the child and, moved with compassion, decided to raise him as her own in the royal palace.

As Moses grew up, he became aware of his true identity and the suffering of his people. One day, he witnessed an Egyptian beating an Israelite slave and, outraged, killed the Egyptian. Fearing for his life, Moses fled to the land of Midian, where he married Zipporah and became a shepherd.

Years later, while tending to his flock, Moses encountered a burning bush that was not consumed by the flames. From the bush, God spoke to Moses, revealing His plan to deliver the Israelites from slavery and lead them to the Promised Land. God instructed Moses to return to Egypt and confront Pharaoh, demanding that he let the Israelites go.

The Ten Plagues Moses, along with his brother Aaron, went before Pharaoh and delivered God's message: "Let My people go." However, Pharaoh's heart was hardened, and he refused to release the Israelites from bondage. In response, God sent a series of ten plagues upon Egypt to demonstrate His power and compel Pharaoh to change his mind.

The ten plagues were:

1. Water turning to blood 2. Frogs 3. Lice 4. Wild animals 5. Pestilence 6. Boils 7. Hail 8. Locusts 9. Darkness 10. Death of the firstborn

Each plague brought increasing devastation and suffering to the Egyptians, while the Israelites were spared. Despite the mounting pressure, Pharaoh remained obstinate, refusing to let the Israelites go until the tenth and most terrible plague struck.

The Passover and the Exodus Before the tenth plague, God instructed Moses to have each Israelite family select a year-old male lamb without blemish, slaughter it at twilight, and apply its blood to the doorposts and lintels of their homes. They were to roast the lamb and eat it with unleavened bread and bitter herbs, dressed as if ready for a journey, with sandals on their feet and staffs in their hands. This meal became known as the Passover Seder.

On that fateful night, the Angel of Death passed through Egypt, killing the firstborn of every Egyptian household, from the lowliest servant to Pharaoh's own son. However, the angel "passed over" the homes marked with lamb's blood, sparing the Israelite firstborns. This final plague broke Pharaoh's resolve, and he finally agreed to let the Israelites go.

In haste, the Israelites gathered their belongings and prepared to leave Egypt, taking with them the dough for their bread before it had time to rise. This is why, to this day, unleavened bread (matzah) is eaten during Passover as a reminder of the Israelites' swift departure from Egypt.

Led by Moses and guided by God in the form of a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night, the Israelites began their journey to freedom. However, Pharaoh's heart was once again hardened, and he pursued the Israelites with his army, cornering them at the edge of the Red Sea.

In a dramatic display of divine power, God instructed Moses to stretch out his staff over the sea, causing the waters to part and allowing the Israelites to cross on dry ground. When the Egyptians attempted to follow, the waters crashed back down, drowning Pharaoh's army and securing the Israelites' escape.

The Significance of Passover The story of Passover holds immense significance for the Jewish people, both as a historical event and as a spiritual metaphor. On a literal level, the Exodus marks the birth of the Israelites as a free nation, liberated from the bonds of slavery and set on a path to the Promised Land. This narrative of redemption and divine intervention has served as a source of hope and inspiration for Jews throughout history, particularly during times of persecution and hardship.

On a deeper level, Passover represents the universal human struggle for freedom and the triumph of the oppressed over their oppressors. The story of the Israelites' liberation from Egypt has resonated with people of all faiths and backgrounds, serving as a powerful symbol of the fight against injustice and the pursuit of human dignity.

Moreover, the Passover story emphasizes the importance of faith, obedience, and trust in God. Throughout the narrative, Moses and the Israelites are called to rely on God's guidance and protection, even in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles. This message of unwavering faith and the power of divine providence has been a cornerstone of Jewish belief and practice for millennia.

Passover Traditions and Observances The Passover story is not only retold but also relived through a rich tapestry of traditions and observances that have developed over centuries. These customs serve to maintain the connection between contemporary Jews and their ancestral past, ensuring that the lessons and significance of the Exodus are passed down from generation to generation.

The Passover Seder The centerpiece of Passover celebrations is the Seder, a ceremonial meal held on the first night (and sometimes the second night) of the holiday. The Seder follows a specific order of rituals and readings, as outlined in the Haggadah, a special text that guides participants through the evening.

During the Seder, families and friends gather around the table to partake in symbolic foods, recite prayers and blessings, sing songs, and discuss the story of the Exodus. The Seder plate, a central feature of the meal, contains six items that represent different aspects of the Passover narrative:

1. Zeroa - A roasted shank bone symbolizing the Paschal lamb 2. Beitzah - A hard-boiled egg representing the festival sacrifice 3. Maror - Bitter herbs, usually horseradish, symbolizing the bitterness of slavery 4. Charoset - A sweet paste made of fruits and nuts, representing the mortar used by the Israelite slaves 5. Karpas - A vegetable, typically parsley, dipped in salt water to symbolize the tears shed by the Israelites 6. Chazeret - Another bitter herb, often romaine lettuce, used in the Hillel sandwich

Throughout the Seder, participants drink four cups of wine, each corresponding to one of the four expressions of redemption mentioned in the Book of Exodus. They also eat matzah, the unleavened bread that recalls the haste with which the Israelites left Egypt.

One of the most engaging aspects of the Seder is the asking of the Four Questions, traditionally recited by the youngest child present. These questions highlight the unique features of the Passover meal and serve as a springboard for discussing the significance of the holiday and the Exodus story.

Passover Dietary Restrictions In addition to the Seder, Passover is marked by a set of dietary restrictions that commemorate the Israelites' hasty departure from Egypt. For the duration of the holiday, Jews refrain from eating chametz, any food made from leavened grains (such as wheat, barley, rye, oats, and spelt). This includes bread, pasta, cake, and most baked goods.

Instead, Jews eat matzah, a flat, unleavened bread made from flour and water, which is baked quickly to prevent it from rising. Many families also have special Passover dishes and utensils that are only used during the holiday to avoid any contact with chametz.

The prohibition against chametz serves as a powerful reminder of the Israelites' exodus and the importance of humility and simplicity. By forsaking the "puffed up" nature of leavened bread, Jews symbolically reject the ego and arrogance that can lead to oppression and injustice.

Counting the Omer Passover also marks the beginning of the Counting of the Omer, a 49-day period that links the holiday to Shavuot, the festival commemorating the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai. Each night, Jews recite a blessing and count the days and weeks until Shavuot, reflecting on the spiritual journey from physical freedom to the receiving of divine wisdom.

The Enduring Message of Passover The story of Passover and its associated traditions have endured for thousands of years, transcending time and place to offer a timeless message of hope, resilience, and the power of faith. In every generation, Jews are encouraged to

Information

| Author | QP-3 |

| Organization | William Corbin |

| Categories | Education , Judaism , Religion |

| Website | - |

| corboo@mac.com |

Copyright 2024 - Spreaker Inc. an iHeartMedia Company