ESPN Senior Writer Howard Bryant, author of Rickey: The Life And Legend Of An American Original

Jun 15, 2022 ·

8m 56s

Download and listen anywhere

Download your favorite episodes and enjoy them, wherever you are! Sign up or log in now to access offline listening.

Description

ABOUT HOWARD BRYANT AND RICKEY On June 7, Mariner Books is proud to publish RICKEY: The Life and Legend of an American Original by Howard Bryant-acclaimed sports journalist and three-time...

show more

ABOUT HOWARD BRYANT AND RICKEY

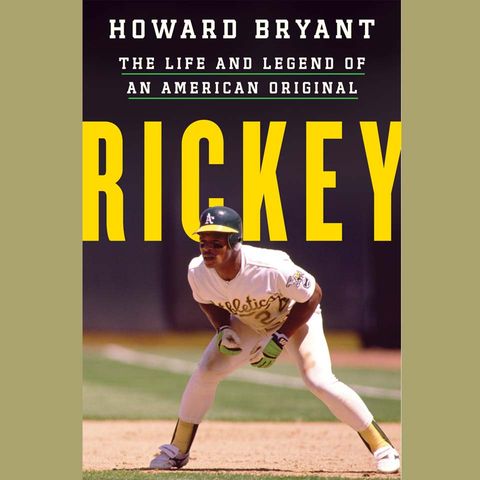

On June 7, Mariner Books is proud to publish RICKEY: The Life and Legend of an American Original by Howard Bryant-acclaimed sports journalist and three-time nominee for the National Magazine Award. Bryant is also the author of nine previous books, including The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron, The Heritage: Black Athletes, A Divided America and the Politics of Patriotism, and Juicing the Game: Drugs, Power, and the Fight for the Soul of Major League Baseball. Now, he offers the definitive biography of Hall of Famer Rickey Henderson, baseball's epic leadoff hitter and base-stealer who dazzled fans over four electric decades in the game.

Few names in baseball history evoke the excellence, dynamism, and curiosity of Rickey Henderson. The panther-like strides off first base. The fingers wiggling, a sign of imminent threat-and then Rickey was gone: the powerful headfirst slide into second base in an eyeblink. On and off the field, Rickey was explosive, unique, electric, and the most polarizing and enigmatic player in baseball.

In the hands of critically acclaimed sportswriter and culture critic Howard Bryant, RICKEY is one of baseball's greatest and most original superstars finally getting his due. Bryant draws on scores of interviews with many of baseball's top players, managers, and professionals, as well as conversations with Rickey himself and his longtime wife, Pamela Henderson. The result is the first and only book to comprehensively cover the baseball legend's life and full career.

Moreover, Bryant chronicles the evolution of baseball over the past five decades into the era of free agency, pay equity for Black players, the emergence of napologetically flamboyant Black athletes like Rickey, and resistance to all of this from baseball's overwhelmingly white establishment. Bryant also tells a broader story of Black America, the promise of the Great Migration from the Deep South to the North and West, and the overall influence of sports on American culture, most notably in the context of Rickey's hometown of Oakland, California.

Rickey's achievements have long been undeniable. From 1979 to 2003, he played 24 seasons in Major League Baseball with nine different teams: the New York Yankees, the Toronto Blue Jays, the San Diego Padres, the Anaheim Angels, the New York Mets, the Seattle Mariners, the Boston Red Sox, the Los Angeles Dodgers, and four separate stints with his original team, the Oakland Athletics. Widely recognized as the sport's greatest leadoff hitter and baserunner, the so called "Man of Steal" holds the all-time major league records for career stolen bases, runs, unintentional walks, and leadoff home runs. Rickey is the only player in the history of the game to have surpassed a combination of 3,000 hits, 2,000 runs, and 2,000 walks-not Ruth or Cobb, DiMaggio or Mantle, Mays, or Aaron. Inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2009 on his first ballot appearance, he was the American League's Most Valuable Player in 1990, a ten-time American League All Star, and the leadoff hitter for two World Series championship teams: the 1989 Oakland A's and the 1993 Toronto Blue Jays.

Grandstander or all-time great?

For many years, Rickey's feats on the field were overshadowed by his reputation as a disrespectful underachiever-a player not fully committed to the game or sufficiently deferential to its hallowed traditions. He delighted fans with "Rickey Style"-antics like his "snatch-catch," his meandering "wide turn" approach to the base line after hitting a home run, and his "pick" at his jersey after a particularly satisfying play. But he was also disparaged as an arrogant, self centered "hot dog" who sat out too many games, nursed dubious injuries, and neglected to learn the names of teammates and umpires. Or as the legendarily dysfunctional Yankees owner George Steinbrenner once memorably put it, Rickey too often was "jaking it" (milking an injury). The situation wasn't helped by the mutually antagonistic relationship between Rickey and the press, his habit of shouting "It's Rickey Time!" as he burst into the locker room, or his often-hilarious malapropisms. While playing for the Yankees, for example, he lived in an apartment across the Hudson River from Manhattan in Hoboken, New Jersey, from which he claimed to be able to see the "Entire State Building."

But as Bryant observes, the amusement at Rickey's expense was unquestionably fed by racial and class prejudice. For "underneath the laughter was the cruelty of inequity," Bryant writes. "There was no question that Rickey suffered from an early reading disability that had not been addressed, that his education had not received adequate attention, and no question that his athletic ability had reduced the academic rigor required of him in the classroom, allowing him to play sports and not learn." [p. 347]

Nevertheless, Rickey's keen intelligence was recognized by none other than renowned Yankees manager (currently New York Mets manager) Buck Showalter, as quoted by Bryant: "Everyone always fixated on Rickey because he wasn't good with words, because he sounded inarticulate, so they assumed he wasn't bright. If you were worried about being made fun of every time you spoke, would you want to give interviews? He spoke in Rickeyisms, but sit down and listen to him talk baseball. Listen to the way Rickey could break down situations, the way he talked about pitchers, the way he used his legs for leverage to take off. Let me tell you, Rickey was a sharp baseball thinker." [p. 334]

When the legend becomes fact

As the years rolled on, and the scope of Rickey's accomplishments started to come into focus, his public image began to change. In part, this was because of baseball's new emphasis on numbers, which were indisputable. Somehow, a player who supposedly was not truly committed to the game was racking up an astonishing set of stats. The Rickey stories were piling up, too, turning him into one of the game's great characters.

Some of the legends swirling around Rickey are true, some are demonstrably false, and Bryant does his best to verify which are which. It's true, for instance, that Rickey was so thrilled by a $1 million signing bonus that he framed the check, forfeiting several months of interest before he deposited it. Notoriously frugal-although he has donated considerable sums to charity and helped to support many family members-Rickey also refused to spend most of the per diem expense money that players receive on the road. Instead, he used it to reward his daughters for their accomplishments in school.

Bryant confirms that one of the most famous Rickey stories, involving Mariner teammate John Olerud, is a fabrication started as a joke by a trainer. As a precaution, Olerud, who had recovered from a brain aneurysm as a young man, always wore a batting helmet while playing defense. Rickey was said to have commented that he once had a teammate in Toronto who did the same thing. "That was me," Olerud was reported to have replied-a testament to Rickey's well known obliviousness to his teammates, which made the story ring true despite its falseness.

Another story, which may or may not be true, recounts the time Rickey sat down on the San Diego team bus in a seat reserved for Tony Gwynn, the greatest of the Padres. As Gwynn came aboard, the other players started to tell Rickey the rules, but the Padres star brushed the whole thing off. "It's okay," he said. "Rickey's got tenure." "Tenure?," Rickey supposedly replied. "Rickey's got sixteen years."

Something else that helped to change Rickey's image was that the sport was catching up to him. Today's teams use terms like "load management," sports corporate shorthand for resting players, a practice Rickey employed for himself when the game wouldn't. It had evolved as managers, GMs, and front offices witnessed unnecessary attrition among players masquerading as machismo or worse, as "professionalism." Case in point: people have been saying for years that Anaheim's supremely talented Mike Trout could turn out to be the greatest player of all time. But after playing at least 157 games for four straight years, Trout hasn't reached 140 games since, and has been plagued by injuries.

The evolution of the game, Bryant says, gave Rickey a measure of satisfaction. Ultimately, he had been right, but he could never forget his bitter memories of fights he did not believe had needed to be fought. Only three players in the history of the sport-Pete Rose, Carl Yastrzemski, and Henry Aaron-had played more games than Rickey, and yet for most of his career Rickey had been accused of not wanting badly enough to play. As an undisputed legend, Rickey would now be celebrated for his longevity, and with the commendations came tacit acknowledgment that he had understood the game better than the people who gave the orders. He was vindicated. Bryant gives the last word to Rickey: "Tell me something. How in the hell you gonna steal fourteen hundred bases jaking it? How could you do what I did, for as long as I did, and say I didn't want to be out there?" [ p. 369]

At age 63, Rickey technically remains an eligible free agent, having never officially retired from baseball. "I think," he said recently, "I could still help a team." [p. 376]

ABOUT HOWARD BRYANT

Bryant is the author of nine previous books, including The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron, The Heritage: Black Athletes, A Divided America, and the Politics of Patriotism, and Juicing the Game: Drugs, Power, and the Fight for the Soul of Major League Baseball. He is a senior writer for ESPN and the sports correspondent for NPR's Weekend Edition. He is a three-time nominee for the National Magazine Award for Commentary and a two-time Casey Award Winner for best baseball book of the year.

https://www.amazon.com/Rickey-Life-Legend-American-Original/dp/0358047315

show less

On June 7, Mariner Books is proud to publish RICKEY: The Life and Legend of an American Original by Howard Bryant-acclaimed sports journalist and three-time nominee for the National Magazine Award. Bryant is also the author of nine previous books, including The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron, The Heritage: Black Athletes, A Divided America and the Politics of Patriotism, and Juicing the Game: Drugs, Power, and the Fight for the Soul of Major League Baseball. Now, he offers the definitive biography of Hall of Famer Rickey Henderson, baseball's epic leadoff hitter and base-stealer who dazzled fans over four electric decades in the game.

Few names in baseball history evoke the excellence, dynamism, and curiosity of Rickey Henderson. The panther-like strides off first base. The fingers wiggling, a sign of imminent threat-and then Rickey was gone: the powerful headfirst slide into second base in an eyeblink. On and off the field, Rickey was explosive, unique, electric, and the most polarizing and enigmatic player in baseball.

In the hands of critically acclaimed sportswriter and culture critic Howard Bryant, RICKEY is one of baseball's greatest and most original superstars finally getting his due. Bryant draws on scores of interviews with many of baseball's top players, managers, and professionals, as well as conversations with Rickey himself and his longtime wife, Pamela Henderson. The result is the first and only book to comprehensively cover the baseball legend's life and full career.

Moreover, Bryant chronicles the evolution of baseball over the past five decades into the era of free agency, pay equity for Black players, the emergence of napologetically flamboyant Black athletes like Rickey, and resistance to all of this from baseball's overwhelmingly white establishment. Bryant also tells a broader story of Black America, the promise of the Great Migration from the Deep South to the North and West, and the overall influence of sports on American culture, most notably in the context of Rickey's hometown of Oakland, California.

Rickey's achievements have long been undeniable. From 1979 to 2003, he played 24 seasons in Major League Baseball with nine different teams: the New York Yankees, the Toronto Blue Jays, the San Diego Padres, the Anaheim Angels, the New York Mets, the Seattle Mariners, the Boston Red Sox, the Los Angeles Dodgers, and four separate stints with his original team, the Oakland Athletics. Widely recognized as the sport's greatest leadoff hitter and baserunner, the so called "Man of Steal" holds the all-time major league records for career stolen bases, runs, unintentional walks, and leadoff home runs. Rickey is the only player in the history of the game to have surpassed a combination of 3,000 hits, 2,000 runs, and 2,000 walks-not Ruth or Cobb, DiMaggio or Mantle, Mays, or Aaron. Inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2009 on his first ballot appearance, he was the American League's Most Valuable Player in 1990, a ten-time American League All Star, and the leadoff hitter for two World Series championship teams: the 1989 Oakland A's and the 1993 Toronto Blue Jays.

Grandstander or all-time great?

For many years, Rickey's feats on the field were overshadowed by his reputation as a disrespectful underachiever-a player not fully committed to the game or sufficiently deferential to its hallowed traditions. He delighted fans with "Rickey Style"-antics like his "snatch-catch," his meandering "wide turn" approach to the base line after hitting a home run, and his "pick" at his jersey after a particularly satisfying play. But he was also disparaged as an arrogant, self centered "hot dog" who sat out too many games, nursed dubious injuries, and neglected to learn the names of teammates and umpires. Or as the legendarily dysfunctional Yankees owner George Steinbrenner once memorably put it, Rickey too often was "jaking it" (milking an injury). The situation wasn't helped by the mutually antagonistic relationship between Rickey and the press, his habit of shouting "It's Rickey Time!" as he burst into the locker room, or his often-hilarious malapropisms. While playing for the Yankees, for example, he lived in an apartment across the Hudson River from Manhattan in Hoboken, New Jersey, from which he claimed to be able to see the "Entire State Building."

But as Bryant observes, the amusement at Rickey's expense was unquestionably fed by racial and class prejudice. For "underneath the laughter was the cruelty of inequity," Bryant writes. "There was no question that Rickey suffered from an early reading disability that had not been addressed, that his education had not received adequate attention, and no question that his athletic ability had reduced the academic rigor required of him in the classroom, allowing him to play sports and not learn." [p. 347]

Nevertheless, Rickey's keen intelligence was recognized by none other than renowned Yankees manager (currently New York Mets manager) Buck Showalter, as quoted by Bryant: "Everyone always fixated on Rickey because he wasn't good with words, because he sounded inarticulate, so they assumed he wasn't bright. If you were worried about being made fun of every time you spoke, would you want to give interviews? He spoke in Rickeyisms, but sit down and listen to him talk baseball. Listen to the way Rickey could break down situations, the way he talked about pitchers, the way he used his legs for leverage to take off. Let me tell you, Rickey was a sharp baseball thinker." [p. 334]

When the legend becomes fact

As the years rolled on, and the scope of Rickey's accomplishments started to come into focus, his public image began to change. In part, this was because of baseball's new emphasis on numbers, which were indisputable. Somehow, a player who supposedly was not truly committed to the game was racking up an astonishing set of stats. The Rickey stories were piling up, too, turning him into one of the game's great characters.

Some of the legends swirling around Rickey are true, some are demonstrably false, and Bryant does his best to verify which are which. It's true, for instance, that Rickey was so thrilled by a $1 million signing bonus that he framed the check, forfeiting several months of interest before he deposited it. Notoriously frugal-although he has donated considerable sums to charity and helped to support many family members-Rickey also refused to spend most of the per diem expense money that players receive on the road. Instead, he used it to reward his daughters for their accomplishments in school.

Bryant confirms that one of the most famous Rickey stories, involving Mariner teammate John Olerud, is a fabrication started as a joke by a trainer. As a precaution, Olerud, who had recovered from a brain aneurysm as a young man, always wore a batting helmet while playing defense. Rickey was said to have commented that he once had a teammate in Toronto who did the same thing. "That was me," Olerud was reported to have replied-a testament to Rickey's well known obliviousness to his teammates, which made the story ring true despite its falseness.

Another story, which may or may not be true, recounts the time Rickey sat down on the San Diego team bus in a seat reserved for Tony Gwynn, the greatest of the Padres. As Gwynn came aboard, the other players started to tell Rickey the rules, but the Padres star brushed the whole thing off. "It's okay," he said. "Rickey's got tenure." "Tenure?," Rickey supposedly replied. "Rickey's got sixteen years."

Something else that helped to change Rickey's image was that the sport was catching up to him. Today's teams use terms like "load management," sports corporate shorthand for resting players, a practice Rickey employed for himself when the game wouldn't. It had evolved as managers, GMs, and front offices witnessed unnecessary attrition among players masquerading as machismo or worse, as "professionalism." Case in point: people have been saying for years that Anaheim's supremely talented Mike Trout could turn out to be the greatest player of all time. But after playing at least 157 games for four straight years, Trout hasn't reached 140 games since, and has been plagued by injuries.

The evolution of the game, Bryant says, gave Rickey a measure of satisfaction. Ultimately, he had been right, but he could never forget his bitter memories of fights he did not believe had needed to be fought. Only three players in the history of the sport-Pete Rose, Carl Yastrzemski, and Henry Aaron-had played more games than Rickey, and yet for most of his career Rickey had been accused of not wanting badly enough to play. As an undisputed legend, Rickey would now be celebrated for his longevity, and with the commendations came tacit acknowledgment that he had understood the game better than the people who gave the orders. He was vindicated. Bryant gives the last word to Rickey: "Tell me something. How in the hell you gonna steal fourteen hundred bases jaking it? How could you do what I did, for as long as I did, and say I didn't want to be out there?" [ p. 369]

At age 63, Rickey technically remains an eligible free agent, having never officially retired from baseball. "I think," he said recently, "I could still help a team." [p. 376]

ABOUT HOWARD BRYANT

Bryant is the author of nine previous books, including The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron, The Heritage: Black Athletes, A Divided America, and the Politics of Patriotism, and Juicing the Game: Drugs, Power, and the Fight for the Soul of Major League Baseball. He is a senior writer for ESPN and the sports correspondent for NPR's Weekend Edition. He is a three-time nominee for the National Magazine Award for Commentary and a two-time Casey Award Winner for best baseball book of the year.

https://www.amazon.com/Rickey-Life-Legend-American-Original/dp/0358047315

Information

| Author | I Am Refocused Radio |

| Organization | I Am Refocused Radio Network |

| Website | - |

| Tags |

Copyright 2024 - Spreaker Inc. an iHeartMedia Company